|

To learn about Luigi Rist, his print art and technique, a number of sources are included on this site.

|

||||||||||

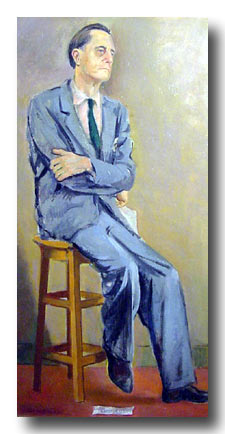

| Portrait in oil of Luigi Rist by Adolf Konrad (Copyright by Adolf Konrad and used with his permission). Photo by Tom Gilchrist. |

![]()

|

LUIGI RISTPrintmaker in the Japanese TraditionBy Barbara Whipple

|

| Photo from Grant Heilman collection |

LUIGI RIST (1888-1959) was an American printmaker whose unique contribution to printmaking lay in combining traditional Japanese woodcut methods with his own unique Yankee ingenuity. During his later life he attained an enviable reputation, winning prizes in major print shows and having the pleasure of seeing his prints added to the permanent collections of such major American institutions as the Butler Art Institute, the Brooklyn Museum, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and in London's Victoria and Albert Museum.

Rist's early training and work as a painter rather than a printmaker did not add up to very much in terms of either satisfaction or recognition; his fine reputation as a printmaker was earned quite late in life. In 1929, when he was 41 years old, he went to Brittany as monitor for the painter Sigurd Skou. By happy accident, well-known Philadelphia painter Morris Blackburn (featured in AMERICAN ARTIST, November 1970) happened to be in Brittany at the same time, and the two men began a friendship which was to last until Rist's death.

One of Blackburn's most important contributions to Rist's career was introducing him to the techniques of the Japanese woodcut print. This germinal event occurred while the two men were on a visit to New York City in the early '30s and Blackburn took Rist to the old Comerford Gallery to see an exhibition of these prints. The prints fascinated Rist so that he returned to study them again and again, and he began experimenting with the medium. Traditionally in Japan, one artist does the drawing, another the carving and another the printing, but Rist did all three steps himself from the very beginning. His two earliest known prints show great simplicity, in marked contrast to the later works when he was thoroughly acquainted with his medium.

In 1941, when he was 53, Rist wrote to Morris Blackburn about his total fascination with the medium: "This damned printmaking has become a very absorbing interest to me. It's a lot of work, hard and uncertain, and when I start printing, I'm off as though on a journey. A batch of work, 40 or 50 prints, takes a good solid week to complete. I get all keyed up, more so than I ever did when painting. And while I'm working I can think and imagine and plan my future blocks. I wonder if it is all worthwhile. It means if I stick to this kind of block printing (and personally I think I should) that it will take all of my time."

That was the year he won his first prizes, and for the rest of his life he was a dedicated printmaker.

There is no doubt that as a printmaker he was unique. While he used traditional Japanese methods, he invented many of his own tools, and the resulting prints have no counterparts, either in Japan or in this country. His subject matter was the flowers, fruits and vegetables of everyday life, many of them grown by his wife, Ida. Taking these simple objects, he made a series of preparatory sketches and drawings in Conte crayon. He deliberately drew the subjects life-size, and the drawings were carefully shaded and toned. By drawing them life-size, and compressing them into the comparatively small area of the woodcut, he gave these subjects a monumental quality.

For his earliest prints, Rist did not use the key, or line, block to establish the linear pattern of the image. Through experience, however, he grew to realize the importance of key blocks, and they were made for all of the later works. Even though it might not be used in the final print, it was required as an outline for the various forms, or for essential lines in the picture, and it was used in controlling the register of impressions from the other blocks.

To make a key block, the outline drawing was traced on a cherry plank, and everything but those fine lines was carved away. Carving such a block could take two weeks, and for the precise and delicate carving required, Rist designed his own knife, made from a blue molybdenum hacksaw blade held in a homemade wooden handle. The blade was pointed in the middle and beveled on one side. Held and guided in the right hand, it was pushed by the thumb of the left hand. It was a tool designed to be used with great delicacy, and enabled the artist to carve the most intricate curves and the thinnest of lines. When these lines had been carved, the remainder of the block was cleared with gouges.

|

|

|

|

| (Labeled #5) | (Labeled #7) | (Labeled #8) | (Labeled #9) |

|

|

|

|

| (Labeled #11) | (Labeled #12) | (Labeled 13) | (Labeled #15) |

|

|

|

|

| (No Label on Block) | (No Label on Block) | (No Label on Block) | (No Label on Block) |

| Photos by Tom Gilchrist. 8 blocks (15 sides plus key block) of "Fruit Dish" courtesy of Carol Faill, Director of the Phillips Museum at Franklin and Marshall Colleger in Lancaster, PA |

All of Rist's blocks were made from cherry wood planks. Cherry wood has an affinity for water-based pigments, a fact known to Japanese printmakers for centuries. Rist would buy the boards from various sources and cut them to size; he would scrape the surfaces of both sides smooth, using a cabinet scraper with his customary extraordinary skill and craftsmanship. His blocks were never sanded, either by machine or by hand, as the scratches of even the finest grit would have been reproduced in the print.

|

"Fruit Dish", 1945, 13 3/4" x 9 3/4". The complete print |

After the key block was cut, decisions were made as to how many blocks would be needed for the completed print. The blocks were carved on both sides, and a typical print might have eight blocks, or 16 sides. Then a series of impressions of the key block were made on lightweight book paper. This paper was dampened overnight between newsprint paper, and it was able to be stretched considerably. Rist described this method in a letter to his friend Robert Kane: "It is extremely important to have the grain of the paper run the same way as the grain of the wood. The impression is pasted on all the blocks lace down with wallpaper paste. After it is dry, dampen it again and peel off one ply and rub on olive oil to make it transparent. Ink in the color separations you want, and cut." This procedure was followed for every block, and is part of the traditional Japanese method. Because Rist's prints required between 50 and 100 impressions to make a finished print (different sections of one block were used for different colors, and frequent overprinting was done), it was necessary to size his Hosho paper with gelatin to enable it to stand up under this kind of punishment. Unsized Hosho is also too absorbent for this type of print. Rist used the following recipe to size his Hosho: ¼ oz. of gelatin, 1/8 oz. of alum and 17 oz. of water. This was soaked first, then warmed in a double boiler. The addition of alum was important, as it acted as a mordant to help "set" the color in the paper, and made for a better colored impression. |

In a letter to Morris Blackburn in November of 1940, Rist describes his method of sizing paper: "I have a stunt in sizing paper that you could also use to advantage. I have a cake pan 6¼ x 12 x 2 inches deep. Put the hot size into the pan (a quart reaches about half way up). Cut the Hosho in half (11 x 17). Start on the far side of the pan and pull paper in the direction of the grain of the fiber. Let the paper ride on top of the fluid, not under it. You will find that the paper soaks up the gelatin like a blotter. Pull the paper through at a steady rate. Pull the paper over to the near side of the pan, which wipes excess size from the sheet as you pull it up. I then put one on top of the other for a half hour or so. You can either hang them up after or lay them out on sheets of newspaper."

|

|

|

|

Photos from Grant Heilman collection |

Before Rist printed an edition, many preliminary proofs had been pulled in order to reach final decisions on color, the order of each impression, the direction the pigment was to be brushed on, how heavy the pressure from the baren (his burnishing tool) should be, and countless other details. (The baren is a Japanese tool and consists of a coil of rope or string on top of a circle of cardboard which is wrapped with a bamboo sheath.) For each edition, Rist prepared a series of "flow sheets" containing all of this information, written out meticulously on lined legal-sized paper. Color decisions were made with the help of a spinning color wheel. The proportions of each color were carefully noted, and directions for mixing them were given by weight, using a chemist's scale. Such careful preparation was necessary because it was never possible to print an entire edition at one time. 30 to 60 sheets of dampened Hosho were all he could handle and bring to completion, facing the ever-present threat of mildew. Detailed though these instructions were, it is unlikely that anyone else would be able to follow them. Rist never canceled any of his blocks, although he did plane some of the early blocks down in order to re-use them.

Rist invented an ingenious device to insure the perfect registry of paper and blocks. He referred to it as a "tympan" (although a tympan actually is the material which is placed between the paper to be printed and the platen or roller delivering the pressure in a press). Rist's "tympan" may be described as follows: A rectangle of wood similar to a printer's chase held the printing block firmly in position with adjustable screws. Hinged to the chase was a piece of glass, with register marks scratched on it. This glass could be opened away from the chase, or lowered over it, like the cover of a book. The printing paper was held lightly to the glass by three clips. The glass, with the paper clipped to it in the proper position, was lowered over the block. The clips were removed, the glass lifted, and the impression made by applying pressure with the baren. Rist had several of these "tympans" of different sizes. Bolts were sometimes set in the edges of the blocks themselves to allow for necessary adjustments caused by slight variations in size, or to allow for warping of the wood. Additional adjustments could be made by screws set into the chase itself.

When one studies these tools that he invented, perfected and used in many, many printing sessions, one cannot but be impressed with his meticulous attention to the details of his craft. This marriage of art and craft is what accounts for the perfection of his prints.

Before a printing session began, Rist always mixed fresh rice paste to mix with his pigments. These are the directions he wrote out for Robert Kane: "One teaspoon full of rice flour to about a half cup of water. Put cold water into a pan; heat but do not boil; mix up flour in the cup with a slight amount of water, then pour some of the hot water into the cup and stir it up. Pour back into the pan of warm water. Keep stirring until thick. Use a double boiler and make fresh paste every day."

Also preliminary to printing, the pigments were measured by weight and mixed according to the proportions he had worked out and written on the "flow sheets." Water was added to the dry pigments until the mixture was the consistency of heavy cream. Using a flat stick, a dab of the rice paste was applied to the area of the block to be printed; with a soft Japanese brush the creamy pigment was also applied to the block, and the paste and pigment were blended with the brush on the block. itself. The type of brush used, the direction of the stroke, all made for different effects. The addition of the paste changed the character of the color from a granular or matt finish to one more brilliant. It also imparted an adhesive quality to the pigment and kept the paper from slipping when printing.

When the block had been inked, it was put into the tympan. The Hosho paper, which had been dampened overnight, was lightly clipped to the glass and lowered onto the block. The clips were removed and the glass lifted, leaving the paper resting on the block. Pressure was applied with the Japanese baren, and the amount of pressure and the manner of rubbing the baren determined the effect and the quality of the color.

When printing finally began, Rist had to continue without letup because of the danger of mildew or of uneven drying of the paper. For the print Dandelions he was handling 60 sheets of Hosho at one time, which would be the maximum. We know he was printing from February 23 to March 19, 1947 (25 days). Dandelions required 44 impressions to complete each print. It must be remembered that each block might have several separate areas which would be printed with different colors or textures, and that frequent overprinting was done to give subtle gradations of tone and special effects.

At one printing session Rist might use 30 to 60 sheets of paper, but he would inspect and discard the prints that didn't satisfy him. Then he would put away the blocks, the flow sheets, and the tracing sheets with the meticulous directions until he needed to make more prints. The record of how many finished prints he had made was written on the flow sheets themselves. The prints, for the most part, are numbered simply "Edition 150," but as far as is known, only two of his prints ever approached that top edition limit.

When he would come back to a block for another printing session, he invariably made changes in the procedure; frequently there are two different sets of "flow sheets" for a given print. Also, as in any hand process, there are variations, and it is interesting to be able to compare differences in individual prints. Rist intended his prints to be hung on a wall and enjoyed, rather than collected in portfolios. He wrote: "No original painting or drawing is made in the sense that one is made to be copied. Rather, this is a method of painting through the medium of printing. Each print becomes an original, having its own individual quality, obtainable by no other means of graphic art expression. The print's colors improve with time. This is due in great part to the paper reverting to its original velvety softness after the strains and compressions of printing, as well as to the gradual disappearance of the sizing paste."

Collectors of Rist prints can attest to the rich, gem-like quality of the color. Adding to their satisfaction is the knowledge of the permanence of both color and paper. The combination of an intricate Japanese process with Yankee ingenuity, plus the love for the natural world which is characteristic of so much American art, has resulted in work of enduring beauty.

![]()

This article on Luigi Rist was the result of collecting and assimilating information for more than a year, during which time she was ably assisted by her husband, Grant Heilman, who took the accompanying photographs. She would like to thank Genevieve Libhart curator of the Community Gallery of Lancaster, Pa., Roberta Strickler, Charles X. Carlson, Morris Blackburn, Robert Kane, and members of the Rist family and their friends who generously assisted her.

[This article is used by permission of her husband, Grant Heilman. The article was published in the August 1971 issue of American Artist. The pictures which accompanied the article were taken by Mr Heilman and he is putting together the original prints to be scanned for this site. The color photos were not part of the article and were taken by Tom Gilchrist.]

![]()

|

STRAW FLOWERSWood Block Color PrintWritten ByLuigi Rist(From the brochure for Straw Flowers)

|

| Print photo by Tom Gilchrist |

Making a print in the Japanese manner is perhaps the oldest known method of printing in color. In this method many blocks are used to obtain a desired result.

The technique of making the print involves three arts: the sketch or drawing, the carving of blocks, and the printing.

The blocks are printed in succession. fifty to a hundred sheets of paper are printed at each session, the impression from a particular block or portion of a block being printed for the entire run before proceeding with the next block or another portion on the same block. As many as fifty or more impressions are sometimes required to complete' a given print. Adding paste changes the character of the color from a granular effect to one, more brilliant It also keeps the paper from slipping when printing and imparts a binding quality to the pigment. When printing a slightly dampened sheet of paper is placed face down on the block, the impression being obtained by rubbing directly on the back of the paper with a slightly oiled pad called a baren. The baren is more or less rigid, slightly convexed and contains a coiled fibre mat covered with a bamboo sheath. The amount of pressure and the manner in which the baren is rubbed determines the effect of the impression in intensity and quality of the color.

In Straw Flowers several drawings were made, eventually evolving into the finished black and white conti drawing. In the drawing an effort was made for simplicity in total arrangement, form, color and space. The mass of flowers was conceived as a whole constructed from the ten minor forms and color of each individual flower. Ten different colored pigments were used in depicting the several flowers in the bouquet, each flower being modulated by a softer grey gradation of each color. A calligraphic effect of dots, lines and dashes printed in a semi-dark pigment was superimposed on the flower forms. To balance this effect, a lacy-like delineation was embossed and printed along the bottom and right edge of the paper wrapping.

Six planks or boards of cherry wood were required as each side of the board is carved, making a total of twelve so called printing blocks. It required twenty six impressions to print "Straw Flowers" and sixty sheets of paper were printed at each session. One hundred twenty prints were made to allow for spoilage and selection.

In Japan three artisans are necessary to accomplish the specialized portions of the work involved, the artist, the wood carver and the printer. In "Straw Flowers" all three operations were accomplished by one artist.

I became interested in this form of art because of its unlimited possibilities in color, calligraphic qualities and the many varied approaches that the medium is adapted to. My first print was made some thirty years ago and I can truthfully state I have barely utilized the possibilities inherent in this printing method.

I was born in Newark, N. J., where I still reside. I studied at the Newark Technical School and the Grand Central Art School in New York. On the whole, however, I have worked along independent lines of artistic investigation.

My use of vegetable and flower subjects is deliberate, as the shapes and forms are basic and varied, and lend themselves to unlimited arrangements, textures, forms, colors and abstraction. Also my prints are limited as to size hence these forms appear on the prints in actual size, which to me gives them added importance, visually and pictorially.

![]()